Blistered Relics | Poojan Gupta

- Lois Valvi

- Dec 18, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Dec 22, 2025

This November at Art Mumbai 2025, artist Poojan Gupta presented a materially driven series of works, solidifying the direction of her practice. Gupta hails from Jaipur, Rajasthan, rhythmically creating between her roots and her recent home in London, UK. As we travel through artistic portals, it's proper to state that Poojan’s large scale sculptures have reawakened past motions, invite our physical touch of the present, and speak critically to a foggy near future. The voice with which she molds ‘discarded objects’ is directly in line with speaking not only to the urgent attention of India’s approach to sustainability, but swiftly unifies with her natural passion for the ancient artistry among her people. She conveys the true story of everyday ritual, humanity by habits, and the dedication of reviving value to the disposed. From one considered rubbish to the lunar glow of an objet sacré, Gupta’s perspective-shift challenges the cultural and societal echoes that are heavily overlapped within India’s viewpoint of art even today.

Holding an MFA from Visva-Bhatari University and a MAAS from Central Saint Martins, her meldable character and skillset have secured her journey as a contemporary artist. Gupta’s steady technique to raise ecological and medical awareness is exactly the proceeding action our ever-current art world needs to participate in, and frankly, at an imperative rate. The challenge of receiving the correct attention from India's industrial sector doesn’t frighten her. In fact, she’s methodically installed herself in the middle of the conversation at this very moment. Gupta confronts the obvious consequences of medical waste by collecting mere pill blister packs - an object we discard rather quickly, and reworks them into light-catching metallic surfaces that encourage viewers to witness our lasting impact as consumers through a gentle lens. Turning the pharmaceutical into poetry is the exact connection that reminds us what contemporary art is meant to strike within us: reflection. The object closely associated with care, health, illness and survival has entered the most site-specific location of the moment, our personal journey through life.

Sensibility of craft combined with global art practices are clearly at the backbone of Gupta’s process. Her detailed focus of interlacing women in her community, however, takes the foundation of her labor to the next level; one we resonate well with here in the Plasmasphere. Gupta’s precision and purpose cannot be shaken. She continues to inspire her main audience - women who have yet to discover their value as artisans, deserving of respect in Western-centered consumerism. A long ongoing theory meant to be tempered with, Poojan Gupta has illuminated the sensory elements of contemporary experience, one that is all encompassing and involves us scattered individuals. Her upcoming works will be assembled for the first time at Jaipur Art Week from January 27 to February 3 2026, a key moment for the native Rajasthani. Upon making crucial the impact of medical waste within India, Poojan’s effect will reach even further, challenging the universal perceptions of Indian culture and our reviving presence in the fine arts. Here lies a pivotal moment we won’t forget; Plasma has collided with a force that's naturally charged a momentum in women’s empowerment, and I’m more than confident it will be hard to stop her now.

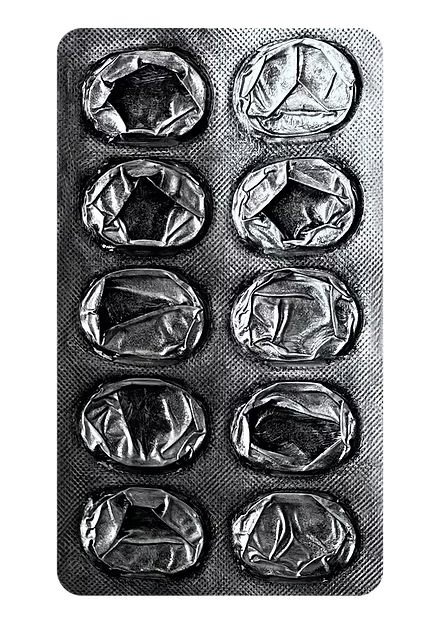

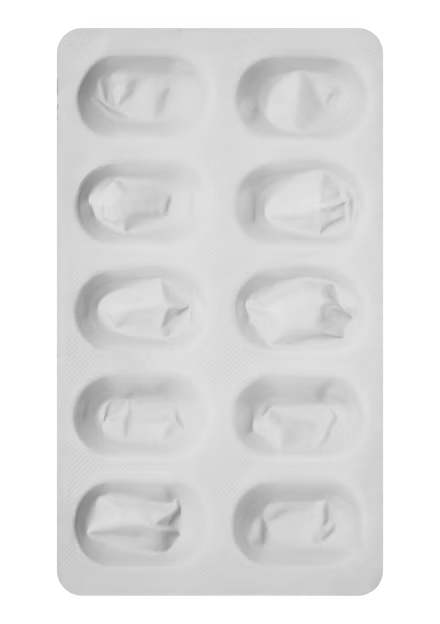

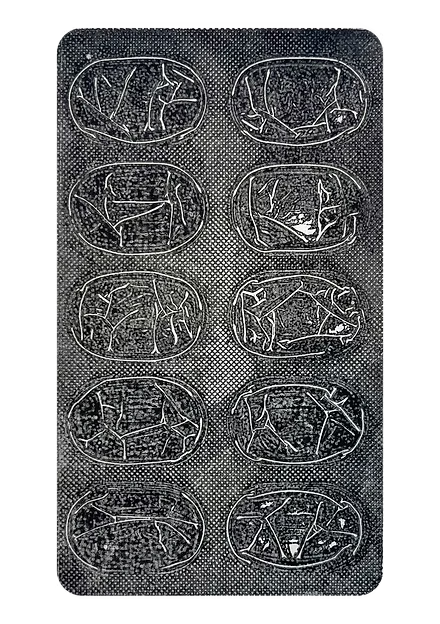

Retained I, brass, 30 x 20 x 1.2 cm. Austrian Cultural Forum, London, June 2024. Courtesy of the artist.

What role does your Hindu upbringing or spiritual background play in how you think about objects, ritual, and transformation in your work?

Realizing that I’m a Hindu actually happened after I came to Oxford. That experience played a big role in making me aware of it. When I was in India, I was born into Hindu Marwari from Rajasthan. I grew up going to temples every day, doing worship, making offerings to God. My family is very ritualistic, so that naturally influenced how I see culture.

When I moved to London in 2022, I was trying to understand new ways of thinking and being in a completely different culture. Then I got connected with the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies which became a turning point in my practice. It helped me return to myself. I realized that even before that, I had been working with ideas of ritual and transformation, but I wasn’t mindful of where my decisions as an artist were coming from. Being at the Centre helped me understand my own background and intentions more clearly. I also began researching how Hindu philosophies and ritual practices influence art, which shaped my work to a great deal since then.

For example, when you perform a ritual or visit a temple, you bring this belief that you will feel better afterward. The aura of a sacred space changes how you experience everything including ordinary objects. Take a coconut. It’s just a fruit, but in India we treat it as an offering before starting something for good luck. That belief turns it from a fruit into the sacred.

"My experiments involves practices such as casting (in aluminium, brass, resin, concrete, silicone, plaster and beeswax), printmaking, drawing, painting, and digitalised forms of reproduction." Courtesy of the artist.

Your use of discarded pharmaceutical blister packs are central to your work. How did you first arrive at that material, and what does it symbolically represent for you personally?

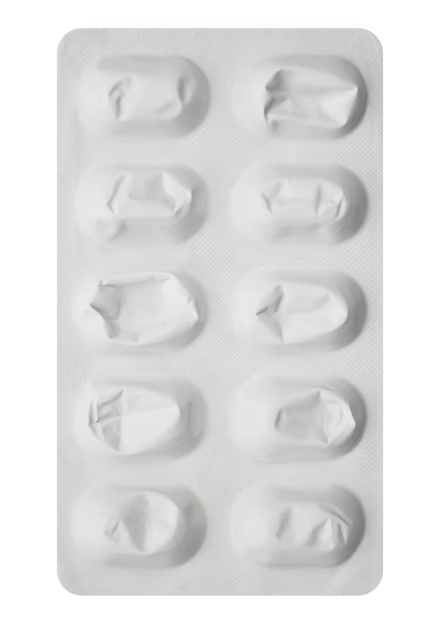

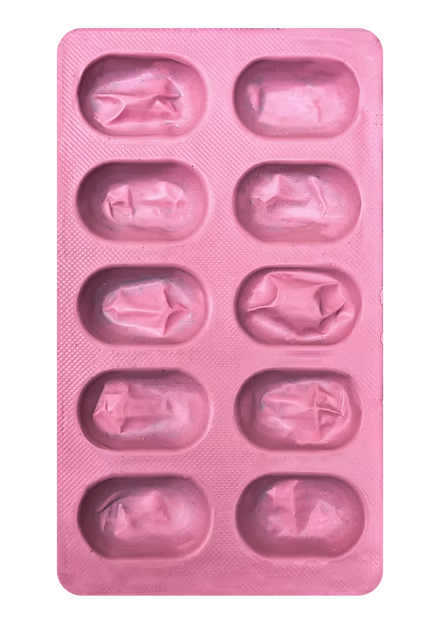

The same way a coconut becomes sacred through belief, I began to wonder if a blister packet could go through a similar transformation. When someone takes a pill, there’s always a subconscious hope for healing or relief. We are taking pills in the form of vitamins or other medicine on a very day to day basis. When the pill is removed and swallowed the empty blister remains as a kind of trace of that act, of that small moment of faith. The dented part marks the exact point when someone pushed the pill out, and I began to think, could that gesture make this discarded object sacred too?

That thought changed how I saw the material. It stopped being just trash or a leftover object. It became a symbol of belief and care, something that once participated in the act of physical healing. So, I began to approach it not for its materiality but for the meaning and transformation it carries of how the discarded material can shift from waste to sacredness. This idea connects firmly to how we make offerings to the divine across cultures. In India, for instance, people tie a sacred thread called Mauli around a tree trunk to make a wish or prayer to gods like Brahma, Vishnu, or Mahesh. In Paris, people lock padlocks on bridges and throw away the key, and in Britain there are old trees with coins hammered into their trunks as votive offerings. All these gestures are about belief and the hope that a wish will come true, even though there is no certainty.

One of my works, titled Wished, stems directly from this. The piece is made of blister packets arranged like a prayer column, inspired by the act of tying Mauli threads around trees. Each empty blister pocket becomes like a small offering or wish. I’ve continued this re-imagination in later settings. For example, I’ve worked with brass versions of blister packets that are now placed in the votive offering cabinets at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, displayed alongside objects that are hundreds or even thousands of years old. Seeing the blister packet in that context, as an offering, gives it a completely new meaning.

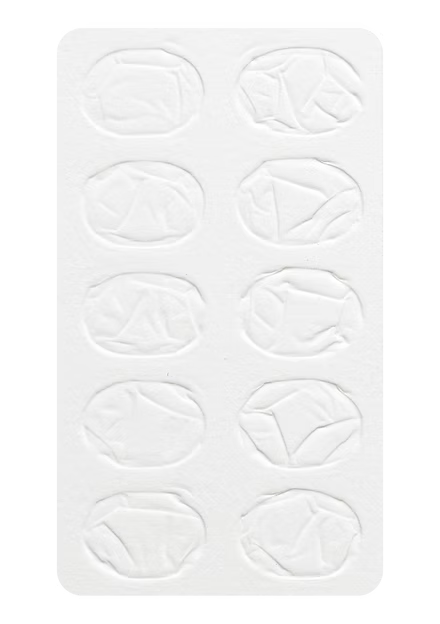

Earlier this year, I also did a residency in Scotland where I worked with porcelain and stoneware. I was thinking about how landfills compress materials back into the earth, and I wanted to imitate that process as a kind of offering too. I used clay which comes from the ground to make small sculptural impressions of blister packets, about 120 of them, so that they could symbolically return to the earth.

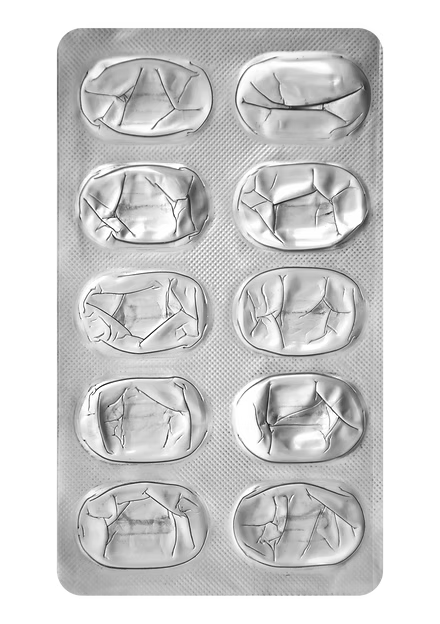

When ordinary becomes sacral (2025), empty blister packs stitched and weaved together, 226 x 148 cm.

Courtesy of the artist.

Are audiences interested in hearing more about ritual or even Hindu beliefs influencing conceptual art?

Yes. I’m actually trying something with this idea in January 2026. There’s an art fair in Jaipur called Jaipur Art Week, and I’m creating a passage installation for it. You know how in temples you walk around the shrine or circumambulate as part of a ritual? I’m building a passage covered with stitched blister packets, where people can walk through it.

By doing that, the audience is unknowingly performing a ritual. If I told them directly to perform one, some people might feel uncomfortable or even offended, which is not my intention. I don’t want to make it about religion or caste or anything restricted. It’s more about the shared act of moving through a sacred space, something that exists across faiths: in temples, churches, dargahs, everywhere. The passage will have a kind of jali pattern, so the light and air move through it like in traditional sacred architecture. Through this work, I’m trying to bring ritual into my practice not just as a visual form but as an experience the viewer physically takes part in. It’s an experiment for me, and I’ll know more once the work is completed and people begin to become participants.

Jaipur Art Week sounds so cool. I’m really glad that’s happening.

It’s funny because I’m actually from Jaipur. I was born here 28 years ago and this is the first time I’m exhibiting in my own city. Since I moved to London, Jaipur Art Week has really started growing, and it’s happening on quite a good scale. There are a lot of creative people getting involved in the process of curation and organizing. So this year I thought, if I’m here, why not take part? I feel like Jaipur is opening up. The art scene is starting to bloom because more thoughtful, engaged creators are coming here. Jaipur has always been rich in miniature painting and traditional arts and you can see artisans all around working on traditional art forms. That traditional scene has always been alive. But what’s exciting now is that contemporary art is starting to find its own space. In the last two or three years, more fairs, exhibitions, and art-related events have begun to pop up. It feels like a new kind of energy is growing in Jaipur.

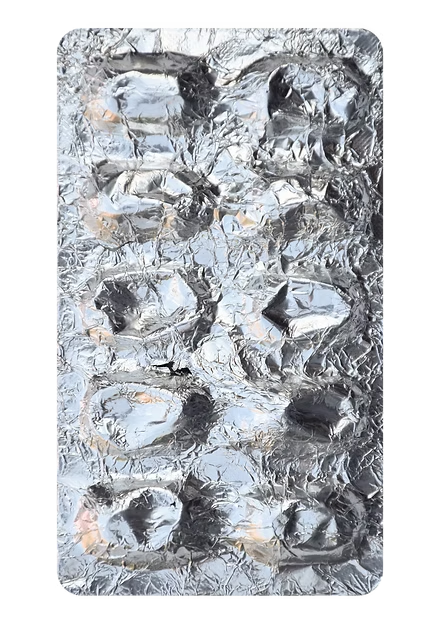

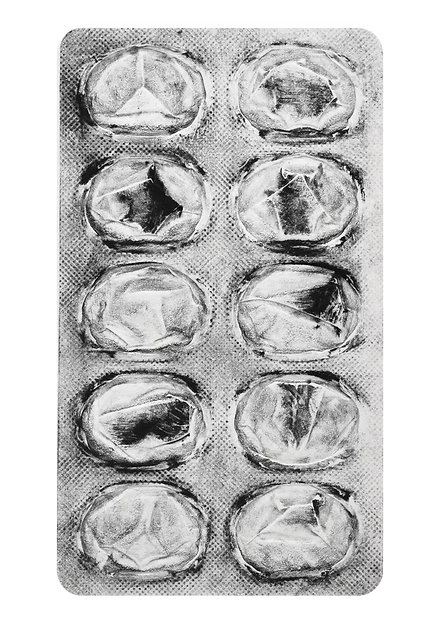

Looking for?, empty blister pack pockets linked together (approx. 25100). Site-specific installation

at Chatéau de La Napoule, La Napoule Art Foundation, France, 2025. Courtesy of the artist.

Your practice transforms waste into objects of contemplation. Could such transformations inspire new models of sustainability or consciousness in Indian society?

I think from that perspective, I wouldn’t say that I’m directly claiming, “I’m repurposing waste into art.” But since the material itself is waste, that idea naturally comes with it. When people look at my work, their questions follow, “What are these? Where did you get so many?” Because normally these blister packets are just thrown away. That moment of curiosity already starts a conversation about waste and conscious disposal. In that sense, my work indirectly encourages sustainable thinking. For instance, in one of my pieces I used around 109,700 blister packets. I try to keep track of the number because it shows the scale of what’s usually discarded without thought.

Now I’m also reaching out to pharmaceutical companies in India, especially in cities like Mumbai and Hyderabad. Many of them produce huge amounts of misprinted or defective blister packets that get thrown out. Some companies are becoming interested in finding better ways to deal with it. The idea is slowly reaching both audiences and producers. It’s not only about how people view waste but also how industries can start thinking more consciously about what they generate. These conversations take time, but I think they’re beginning to open a new level of awareness in India. Blister packets are very strong and resistant; they can’t easily be burned or destroyed. I’ve began experimentations and been looking for industrial ways to work with the material which may turn into a potential solution.

Do you imagine more future works that involve versatile practices?

Touch has always been a big part of my practice as I work with installations. I feel that looking at an installation should be an experience because it meets you at a human scale, so I’m definitely interested in finding new ways for people to engage with the work. Earlier this year, I did a residency in France at La Napoule Art Foundation. I installed a piece inside a castle turret that responded to sea waves. The movement of the blister chains created sound all the time. That experiment made me curious about sound as a material in itself and I’d love to collaborate with a sound artist in the future. Another idea I’m working on is a large carpet made of blister packets, something people can walk on barefoot. It would feel slightly textured like a meditative mat, and welcome them to reflect on the waste we step over the streets every day without noticing.

Lastly, I started making small jewelry pieces for myself to wear at exhibition openings, and that led me to research charm amulets and how belief systems are tied to wearable objects. That’s now become its own project called Worn. I’ve been making belts, bracelets, and neckpieces using blister packets, not as decorative jewelry but as wearable sculptures on what we value and why we wear certain objects for belief or meaning. I’m also collaborating with a fashion designer on a couture piece in brass. We’re treating it like an artifact rather than clothing which carries intention and consciousness beyond just style.

Worn, 2024 (ongoing series). Courtesy of the artist.

How have networks or mentorships shaped your direction as a woman artist in both India and the UK?

I think the answer has both positives and negatives. As a woman in India, you’re expected to behave in certain ways, especially if you come from a traditional family. From childhood, my mother has been my biggest supporter and role model. She’s the one who has given me the strength to raise my voice. My parents are actually very progressive. They’ve trusted me to travel alone, to study abroad, to live independently. But in India, for a daughter to have freedom still feels like something that needs to be “allowed.”

That mentality creates constant challenges for women who want to pursue art seriously. It’s not just about ambition but safety, permission, and perception. Men can move freely, work late, and explore without fear. For women it’s different. We have to be alert to that gaze and feeling of vulnerability. In my own practice, I often work in metal markets or with foundries where most artisans are men. In the bronze casting studio I currently work at in Jaipur, there are twelve people: eleven men and me. People see the finished artwork, but they don’t see what it takes to make it. The social negotiations, the risks, the courage to simply show up in those environments. But I also believe that despite these barriers, the right networks and people can really change things. For example, when a pharmaceutical company in India approached me to create an installation from their waste, it opened a whole new course of conversations and opportunities.

Similarly, in London, my work Wished won the Maison/0 Award by LVMH. That recognition pushed my practice to another level. So networks do matter, but I see them differently now. To me, a “network” isn’t about attending every private view or collecting business cards. It’s simply the right people knowing your work. Many art schools tell students to go to openings and ‘’network”. But they often forget to say the most important thing: you first have to make yourself authentic. Once your work is genuine, people will find you. If you chase people, it doesn’t work. Authenticity doesn’t come from chasing, it comes from focusing deeply on what you do. The rest follows naturally. That’s how I see networks and mentorship now: they grow from within your work, not from external chasing. Once you focus on the practice, everything else begins to build around it.

One of my professors told me something I still live by: “Don’t focus on the career. Focus on the practice. Once your practice is strong, the career will follow.” I think that’s true. A lot of younger artists are preoccupied with visibility. For three years, when I was uncertain about my direction, I completely stopped using social media. I realized that consuming too much visual content could involuntarily influence me, and I didn’t want my ideas to become a mix of others’. That decision really paid off. It helped me understand where my work stands.

Looking towards the near future, how do you hope to reach and inspire the next generation of women artists in South Asia and abroad?

I think a lot of it begins at home. I was the first woman in my family to go out and actually pursue art as a career, so that already started a shift. Now when younger cousins see me working and exhibiting, they’re beginning to ask their parents, “If she can do it, why can’t I?” I hope to become a voice for those women in India who are still deciding what to study or what kind of future they want for themselves. What I really want is to reach women who are outside the art world too. Plenty see art as a pastime and not something they can build a career on. I want them to realize that art isn’t just a hobby, and like every profession it demands the same effort and dedication.

Photo Credits to Rudresh Arora Artist Website: https://www.poojangupta.com/

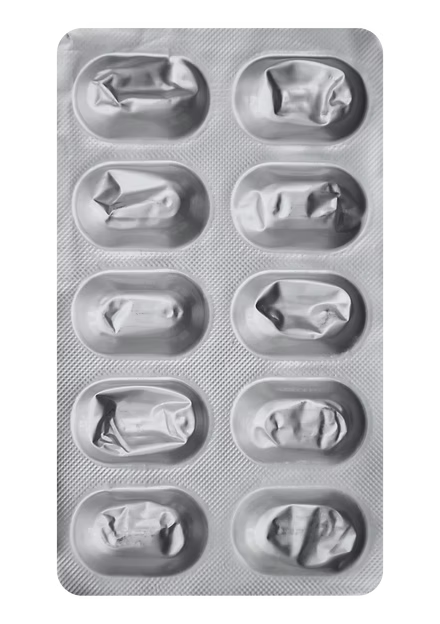

Wished, empty blister pack pockets joined together (approx.109,700), steel structure, connector rings and mesh, 350 x 80 x 80 cm. Central Saint Martins, UAL, London, June 2024